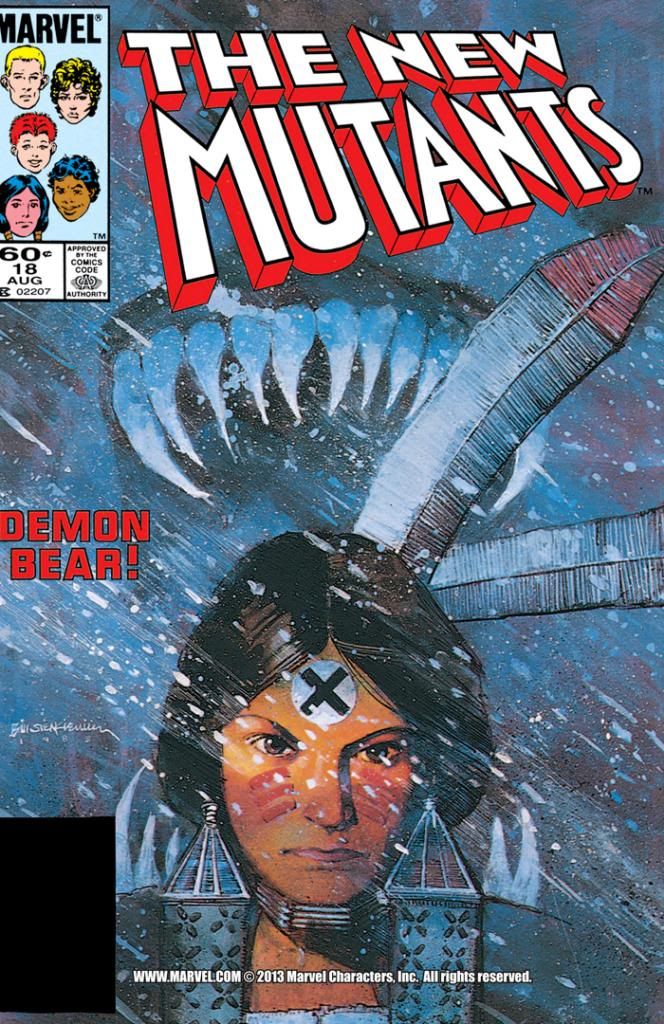

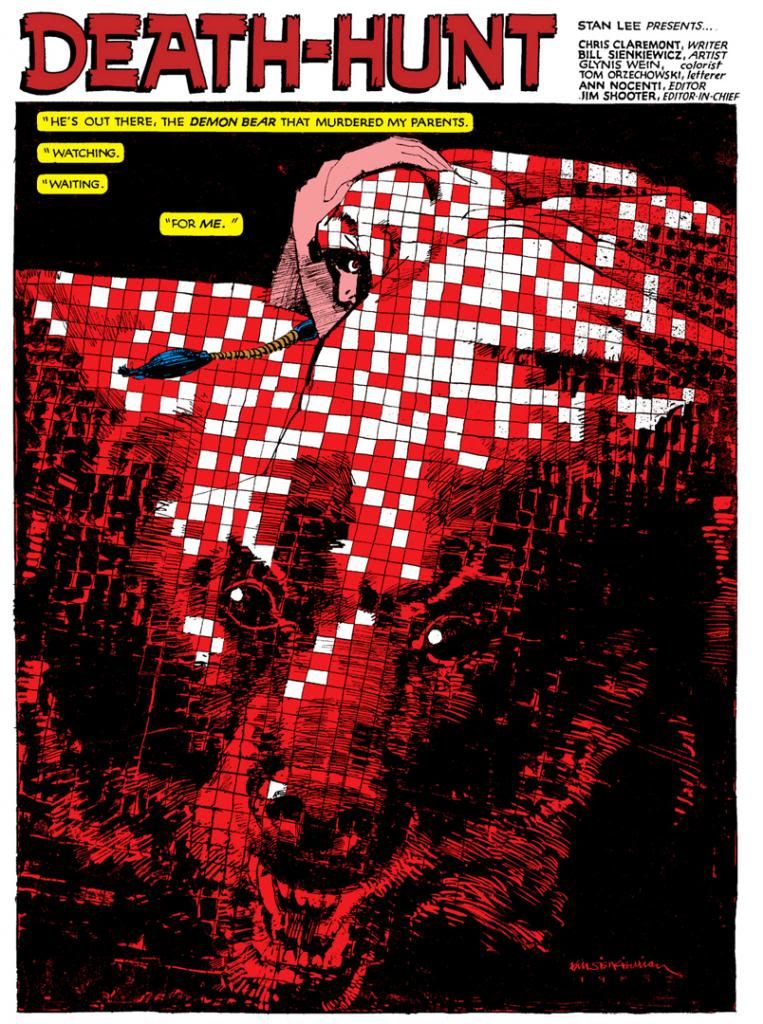

It kicks off in The New Mutants #18 (August 1984) with a painted Sienkiewicz cover that wastes no time announcing the book is something special. Not the one you've been used to and slightly disappointed by for the last six months or so. The Sienkiewicz Dani gazes intently at the reader, with a face recognizable as the Bob McLeod character, but now with thin-lipped determination and more culture-specific accessorizing (the forehead X is especially clever). Behind her, however, the fangs of discord. Danger in the snow. Sienkiewicz brings a painterly approach with a strong design sense as well.

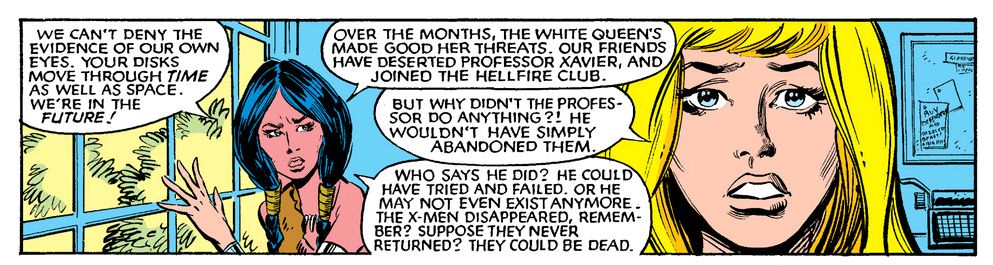

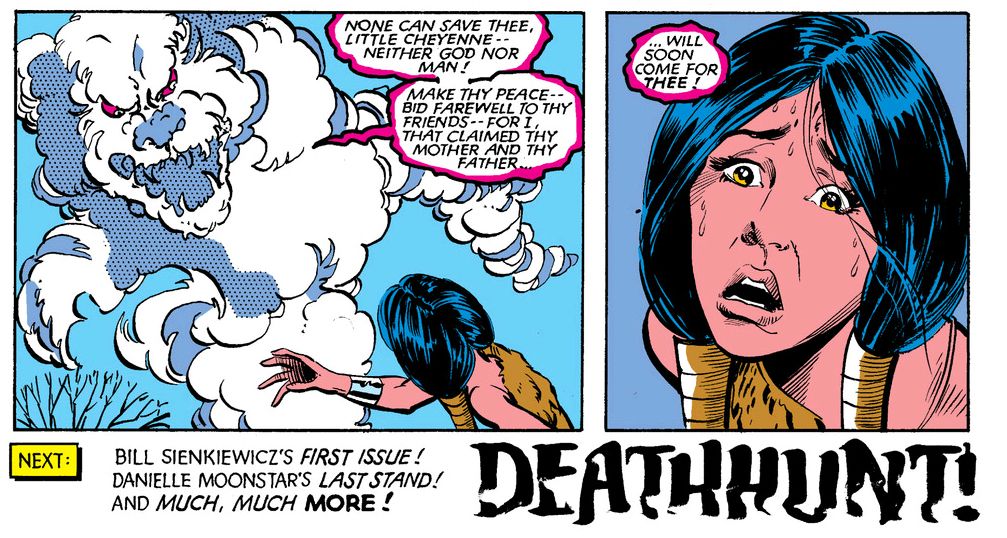

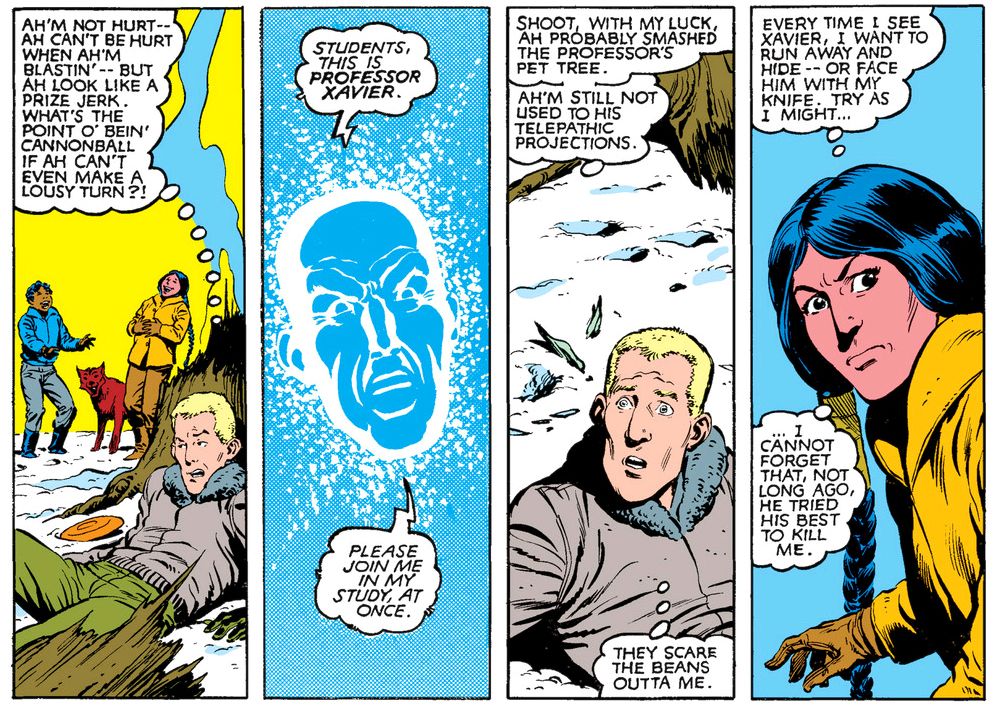

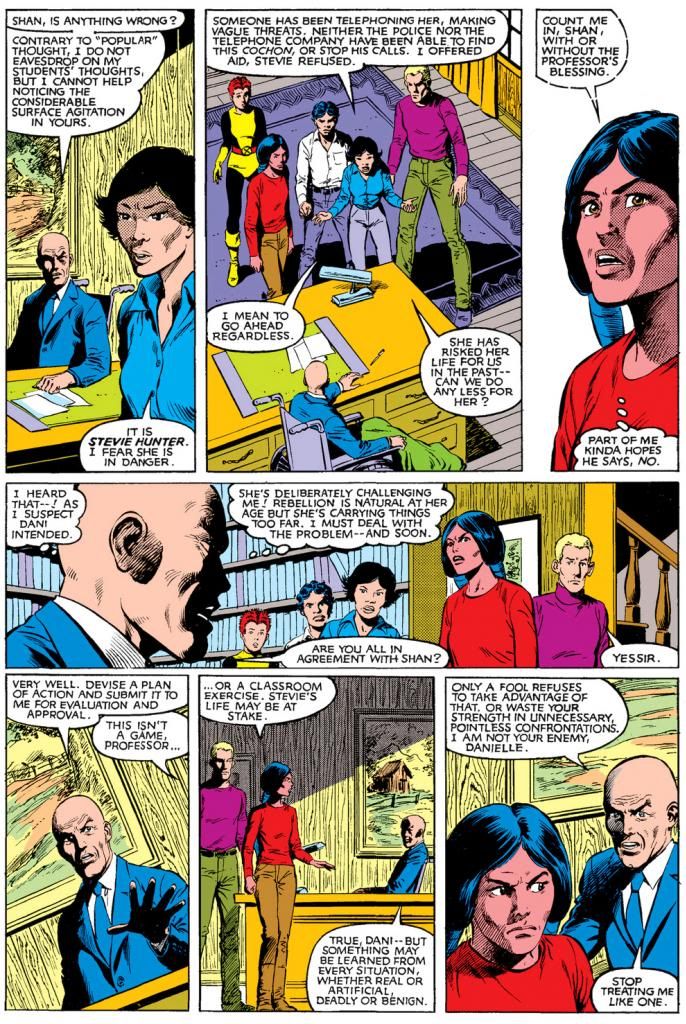

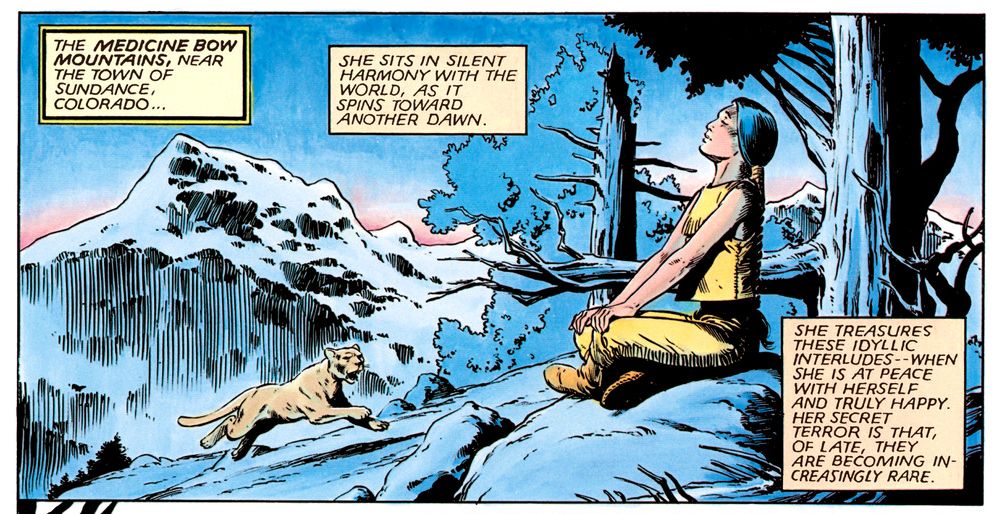

If you'll remember, way back in the first issue, Dani told Rahne a little bit about herself and the story of how her parents vanished while possibly fighting a mystical bear. It was one of Dani's earliest moves towards becoming the book's standout character. Then, in the third issue, we got to see the bear itself. Kind of. It was more than likely a mind-game the Brood-infected Professor X was playing on Dani, drawing out her worst fears. Then the book went off on a Team America-Romans-living-in-South-America-Magik tangent and no one mentioned Dani's magic bear for a while.

Well, readers might have forgotten the exact details, but rest assured, Claremont did not. A master of the slowly developing subplot, Claremont returned to this little biographical tidbit and spun it into a unique tale as psychological as it was action-packed, a genre-stretcher that took the kids out of their cozy heroic adventure home and tossed them into the deep, dark woods we like to call horror. If this had been a DC book and Vertigo had existed in 1984, "The Demon Bear Saga" with its dripping blood and ever-shifting dreamscapes would have been a perfect fit. And Seinkeiwicz, who must have bought india ink by the tanker truck-full, was just the guy to illustrate it.

Why a bear? What am I, a cultural anthropologist? What little I know about Native American culture comes from a single university folklore class, reading a few histories and novels like Tom Berger's novel Little Big Man and the essay They Have Not Spoken: American Indians in Films by Dan Georgakas. In short, I know just enough to make an ass of myself. To make matters worse, I'm going to rely on the Internet. Apparently, bears are very powerful animals. Magically powerful. There's a wonderful story in which a great bear chased some girls (perhaps Lakota, not Cheyenne, but many tribes tell variants of this one), who took refuge on a rock. They prayed that the rock would grow and save them from the bear. It did and they took to the sky as the Pleiades (also known in Greek myth as the "Seven Sisters"). The bear in its hunger and rage clawed the sides of the rock, leaving it scarred. Today we know this rock as the Devils Tower, Wyoming.

The point is, bears figure in a lot of myths and stories, so a bear makes an excellent choice for Dani's spirit antagonist.

One aspect of Marvel's mutant books is how mutant powers and the reactions of those manifesting them and by society at large as a response to these powers can be read as an allegory on race, gender, sexuality, or any kind of "othering." The sexuality reading has ascendancy these days, especially in light of its treatment in the X-Men films, where Iceman's parents ask him if he's tried not being a mutant (X2: X-Men United, 2003) and where Mystique anachronistically tells Beast to be "mutant and proud" in 1962 (X-Men: First Class, 2011). The scene where Beast has his mutant status inadvertently revealed is especially evocative of an outing. Reinforcing this is the trope within the comics themselves that mutant powers typically manifest at puberty.

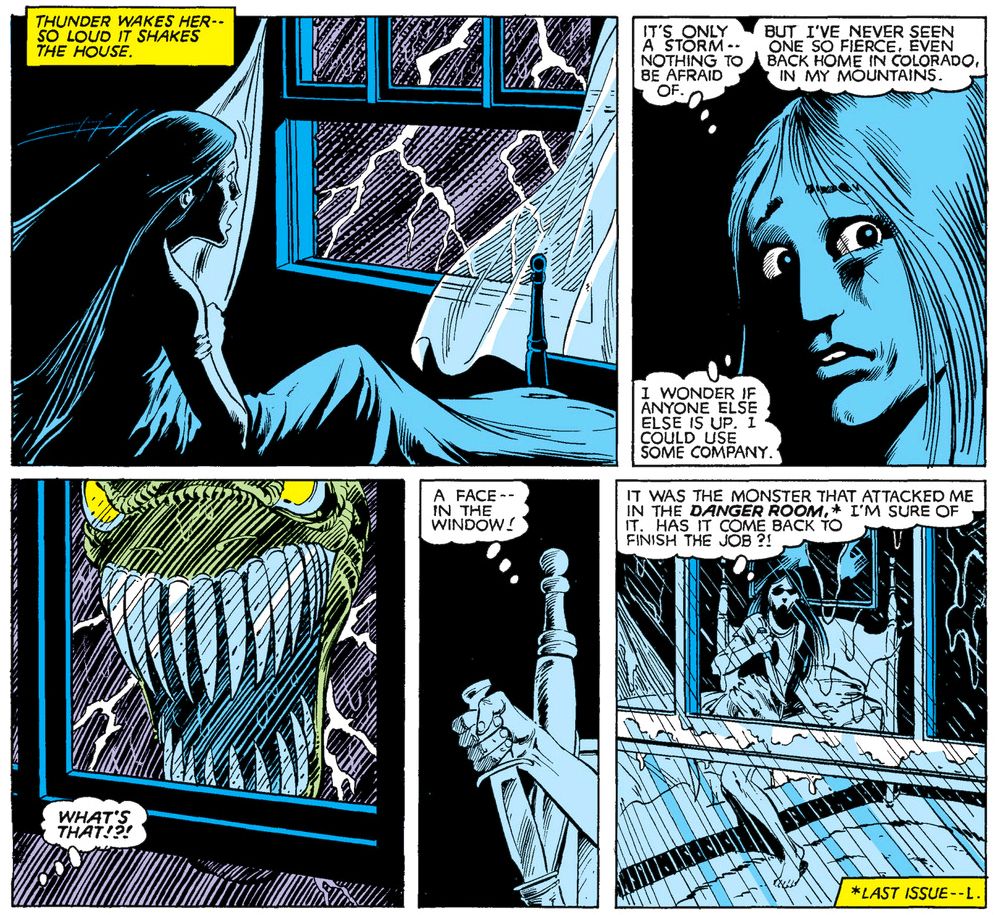

Appropriately, “The Demon Bear Saga” is a story rife with

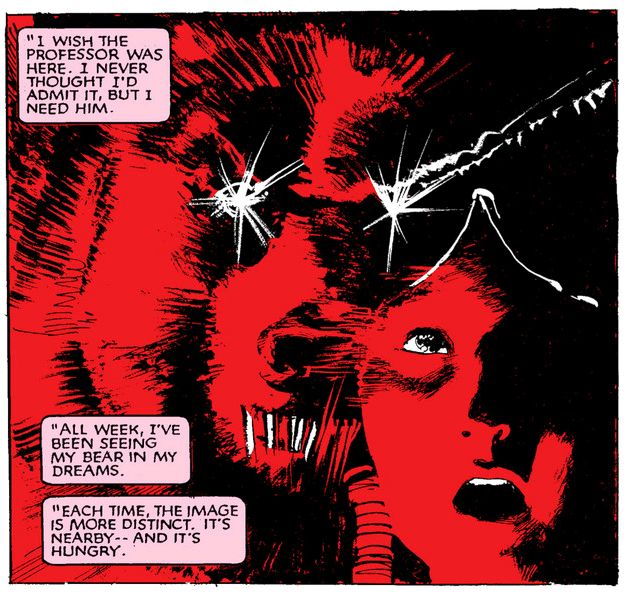

sexual symbolism, no doubt resulting from a happy synergy between Claremont, operating at the utmost of his considerable skills as a writer and an insightful artist in Sienkeiwicz, one open to expanding the literary vocabulary of superhero comics through experimental techniques. In the opening splash

page, Dani cowers in bed while Claremont has her narrate her plight and Sienkeiwicz and colorist Glynis Wein cover her in a red

sheet imprinted with a dream image of the demon bear. It’s a shocking image, our favorite mutant

swaddled in what appear to be blood-soaked sheets and the red motif would recur, reappearing with the bear imagery as Dani thinks about her most recent dreams involving her foe in a later scene and again when Dani ritualistically paints her face as she prepares for the climactic confrontation.

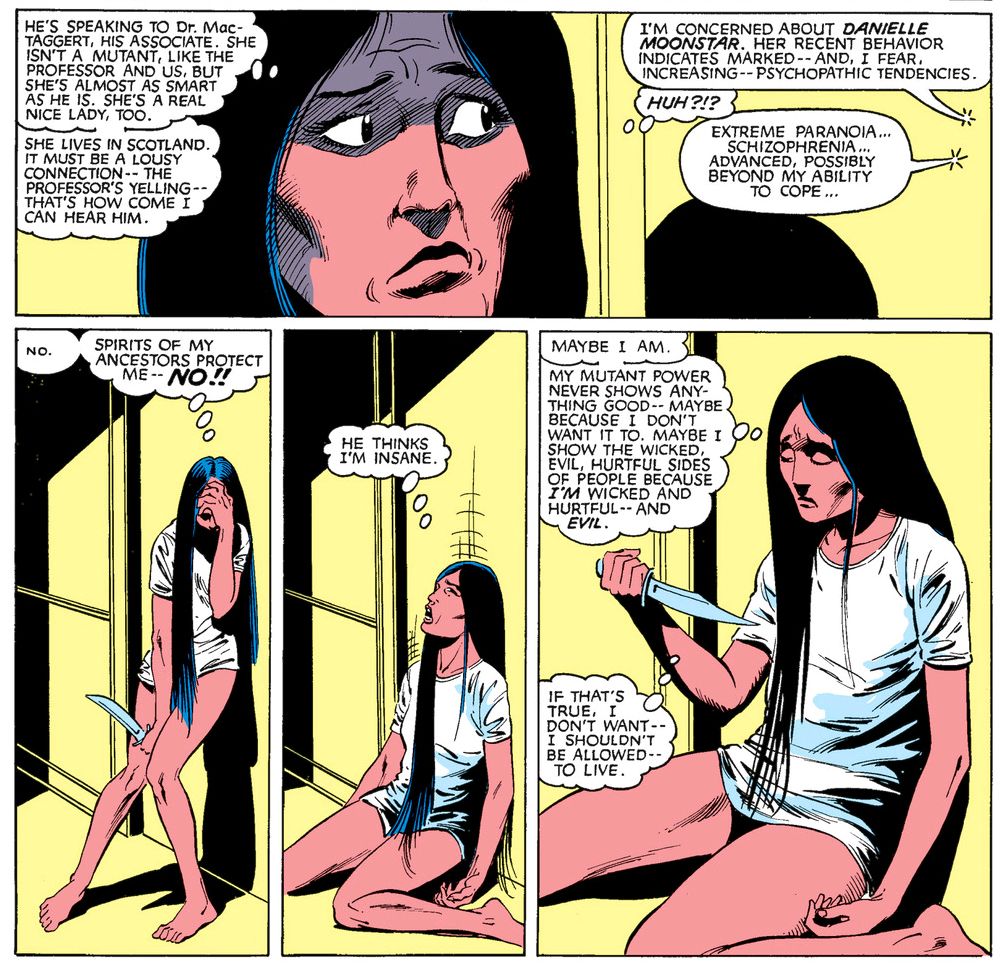

Significantly, the bear enters Dani’s life at the same time her mutant powers appear, roughly around puberty as per Marvel's mutant mythology—one of her first acts as a full-fledged mutant is to show her parents their apparent deaths at the bear’s claws, which becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. In the real world, there is another power, another type of becoming, of a great and personal change, that fulfills itself at puberty through blood. You can find it providing one subtextual reading of the fairy tale "Little Red Riding Hood" and horror authors and creators before Claremont and since have used it more overtly to add resonance to their works. Steven King and Brian DePalma used this theme to great effect in both the novel Carrie (1974) and its classic film adaptation (1976). More recently, screenwriter Karen Walton explored these associations in the werewolf film Ginger Snaps (2001), directed by John Fawcett. Dani’s horrified response to developing a power she lacks the experience and understanding to control, and one that causes her parents’ deaths is ultimately a signifier of her ambivalent response to having matured sexually in a patriarchal society that marginalizes her as a woman. Dani's real struggle is to overcome this ambivalence and the shame and self-loathing that results.

Unfortunately for Dani, her parents were unable to protect her at a time when these changes were at their most intense. In fact, the root of Dani's guilt is that this maturation, this physical change, visited in her desires or thoughts she equates with the bear's utter destruction of her parents. Feeling betrayed by her body, she has taken responsibility at having violated the nuclear family. But because she is essentially a strong, brave young woman, after an initial period of understandable dread, she will attempt to attack the problem head-on. It won't be easy, and requires an elaborately ritualistic preparatory regimen.

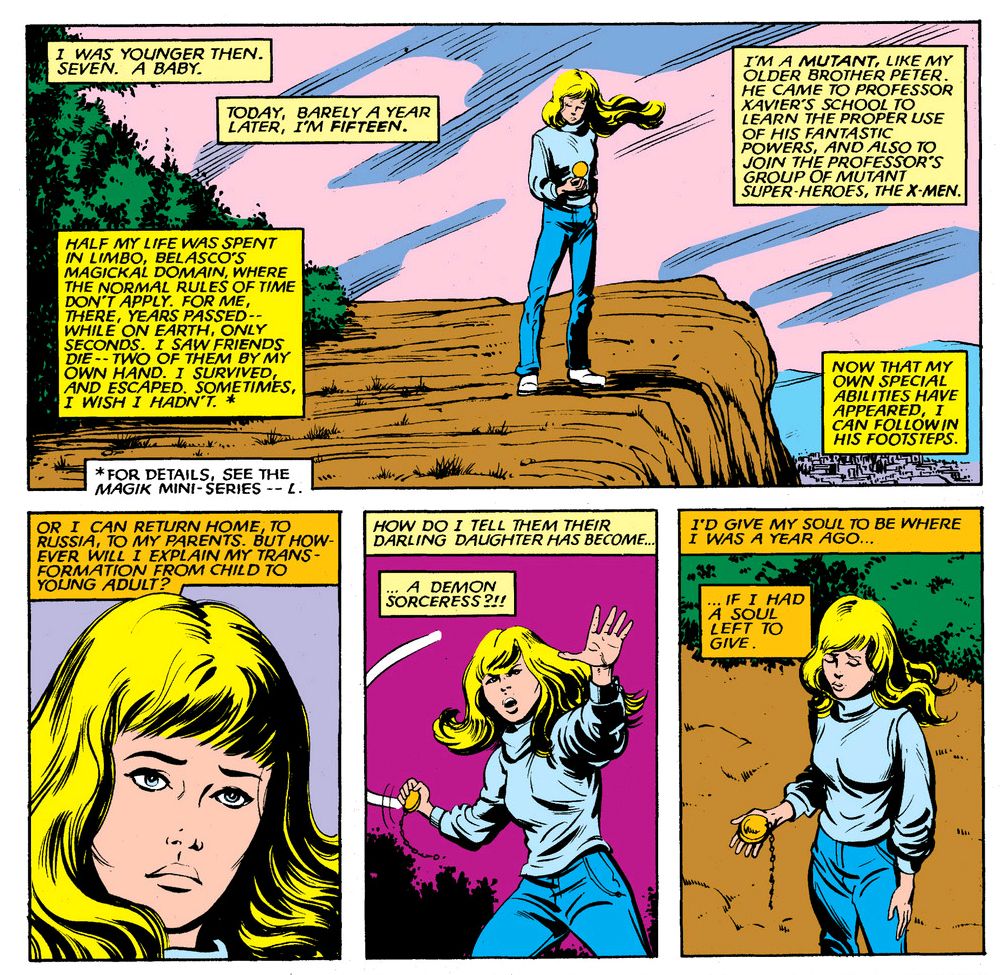

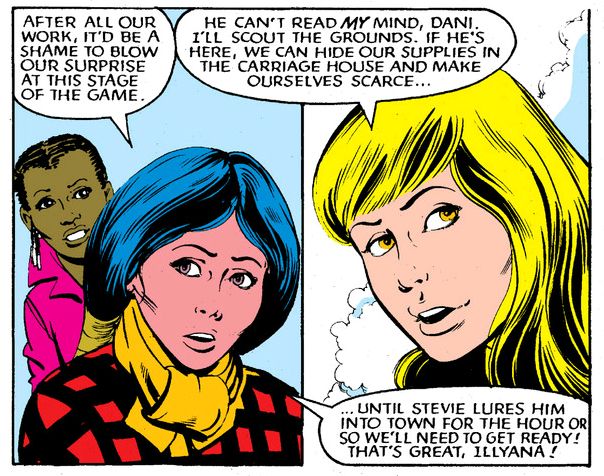

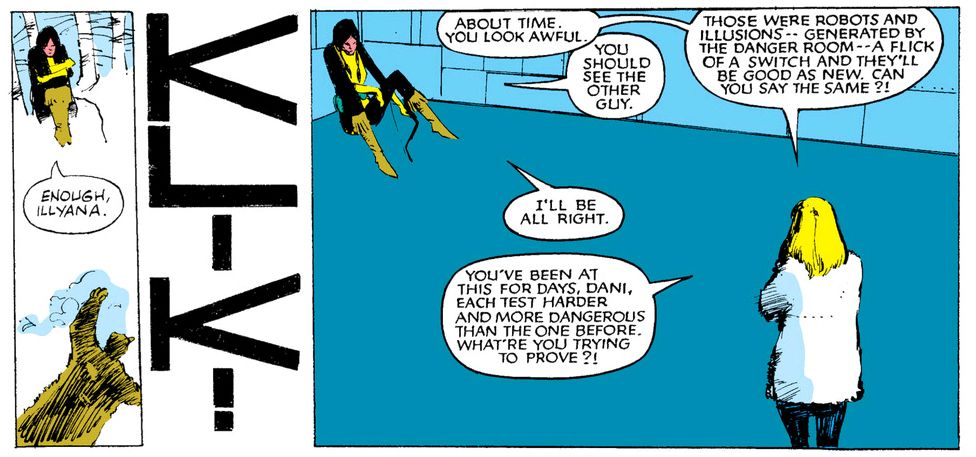

In preparing herself to contest the bear, Dani turns not to her chaste and inexperienced friend Rahne, but to the wiser-- and therefore, no longer innocent-- Magik. Magik, having spent her formative years in Limbo, is an enigmatic figure, and an outsider. She is also symbolically corrupt in the same way Dani believes herself to be. Not quite human, not quite mutant, not quite demon. Dani reveals through her narration that she's not even particularly close to Magik-- Illyana is best friends with Kitty Pryde-- so this makes her choice of confidante all the more telling. But such is Dani's confused acquiescence to the cultural idea there is shame and uncleanliness in having become fertile that she is unable to tell even Magik her true motivation. The more experienced Magik provides Dani an outlet for exploration and experimentation as she seeks to understand the nature of her new-found desires and physically ability to feel and act upon them.

|

| Chris Claremont, scipt/Bill Sienkiewicz, art/Glynis Wein, colors (The New Mutants #18, August 1984) |

Significantly, the bear enters Dani’s life at the same time her mutant powers appear, roughly around puberty as per Marvel's mutant mythology—one of her first acts as a full-fledged mutant is to show her parents their apparent deaths at the bear’s claws, which becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. In the real world, there is another power, another type of becoming, of a great and personal change, that fulfills itself at puberty through blood. You can find it providing one subtextual reading of the fairy tale "Little Red Riding Hood" and horror authors and creators before Claremont and since have used it more overtly to add resonance to their works. Steven King and Brian DePalma used this theme to great effect in both the novel Carrie (1974) and its classic film adaptation (1976). More recently, screenwriter Karen Walton explored these associations in the werewolf film Ginger Snaps (2001), directed by John Fawcett. Dani’s horrified response to developing a power she lacks the experience and understanding to control, and one that causes her parents’ deaths is ultimately a signifier of her ambivalent response to having matured sexually in a patriarchal society that marginalizes her as a woman. Dani's real struggle is to overcome this ambivalence and the shame and self-loathing that results.

|

| Chris Claremont, scipt/Bill Sienkiewicz, art/Glynis Wein, colors (The New Mutants #18, August 1984) |

Unfortunately for Dani, her parents were unable to protect her at a time when these changes were at their most intense. In fact, the root of Dani's guilt is that this maturation, this physical change, visited in her desires or thoughts she equates with the bear's utter destruction of her parents. Feeling betrayed by her body, she has taken responsibility at having violated the nuclear family. But because she is essentially a strong, brave young woman, after an initial period of understandable dread, she will attempt to attack the problem head-on. It won't be easy, and requires an elaborately ritualistic preparatory regimen.

|

| Chris Claremont, scipt/Bill Sienkiewicz, art/Glynis Wein, colors (The New Mutants #18, August 1984) |

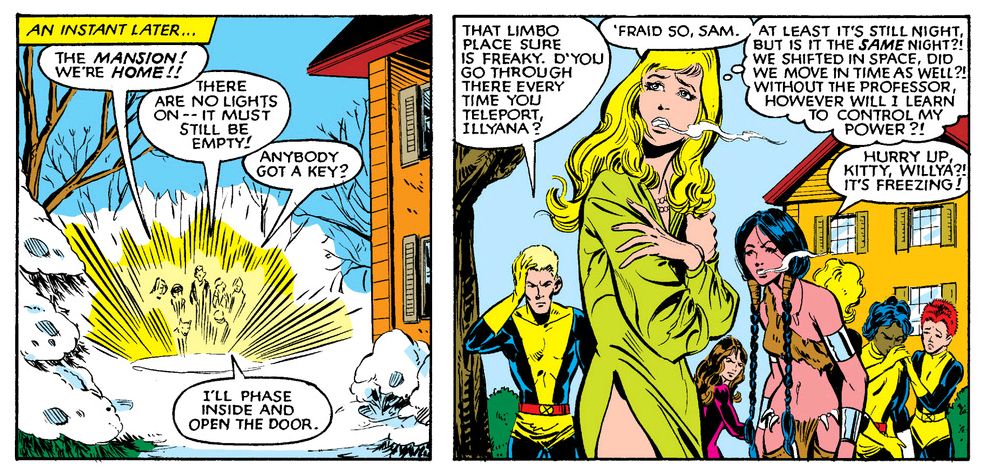

In preparing herself to contest the bear, Dani turns not to her chaste and inexperienced friend Rahne, but to the wiser-- and therefore, no longer innocent-- Magik. Magik, having spent her formative years in Limbo, is an enigmatic figure, and an outsider. She is also symbolically corrupt in the same way Dani believes herself to be. Not quite human, not quite mutant, not quite demon. Dani reveals through her narration that she's not even particularly close to Magik-- Illyana is best friends with Kitty Pryde-- so this makes her choice of confidante all the more telling. But such is Dani's confused acquiescence to the cultural idea there is shame and uncleanliness in having become fertile that she is unable to tell even Magik her true motivation. The more experienced Magik provides Dani an outlet for exploration and experimentation as she seeks to understand the nature of her new-found desires and physically ability to feel and act upon them.

|

| Chris Claremont, scipt/Bill Sienkiewicz, art/Glynis Wein, colors (The New Mutants #18, August 1984) |

Bears are largely masculine figures, and in order to confront hers, and with Magik playing the role of sexual agent, Dani must cross genders (at one point she jokes with Magik, "You should see the other guy," guy being sometimes gender neutral, but generally a masculine noun; Dani clearly identifies herself here as a guy at least in a symbolic sense), or at least add male characteristics to her own innate female identity. In the Cheyenne tradition, men acted as hunters and warriors, but one might reject this path and begin living as a woman. Dani subverts, or rather, inverts this by taking on the role of hunter-warrior, but not without symbolically daubing herself with her own menstrual blood (I'm also reminded of the scene in Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar, where her protagonist, Esther, bloodies the nose of her attempted-rapist and he similarly paints her face with it), represented as red war paint. Only then is she prepared to do more than cower in bed or react in fear. Thus cloaked in the accouterments of maleness, Dani is free to act, to slay the bear.

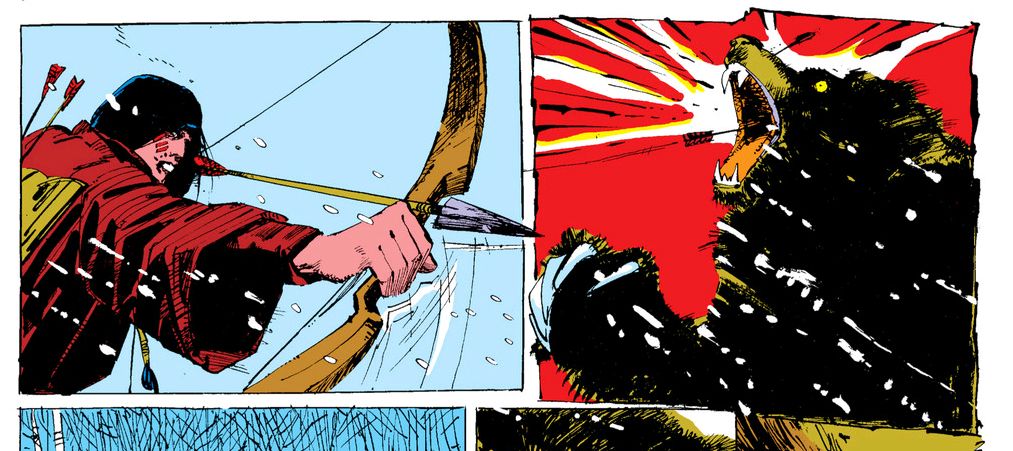

For this, Dani uses a weapon associated with Native Americans by history and custom, the bow and arrow. The arrow is phallic. It penetrates and Dani has made herself expert in its use thanks to her training sessions with Magik. And yet Dani is also reminiscent of Diana of Roman myth, from the similar names, to the choice of weapon, to the time at which she forces this confrontation-- that is, night time. Diana has associations with the moon. She is also the goddess of the hunt. And of chastity. It's worth noting, too, that Artemis, the Greek version of Diana, is goddess of childbirth as well. In order to battle the bear, Dani requires herself to embody both sides of the gender dichotomy. In this way she becomes both her own father and mother.

|

| Chris Claremont, scipt/Bill Sienkiewicz, art/Glynis Wein, colors (The New Mutants #18, August 1984) |

The confrontation with this male presence occurs in snowy woods. The snow, of course, is white. This can be seen as purity, but snow may also be representative of death. Woods hide mysteries and figure in many fairy tales as places where terrible things may happen to children. Here, Dani-- drawn by Sienkiewicz as a silhouette, all her sexual characteristics blotted out or hidden-- calls out the bear as "butcher of innocents," which we can also understand as "butcher of innocence." The dialogue here is artificial and lacks the voice of a teenage girl. It's more in the epic tradition, something Beowulf might say to Grendel in translation. The bear then appears, and Wein colors it various shades of purple, representing pain or bruising, while on the next page it's a more naturalistic brown as it has fully manifested before Dani. Its threat is no longer confined to the subjective space of Dani's dreams but rather has become real and potent.

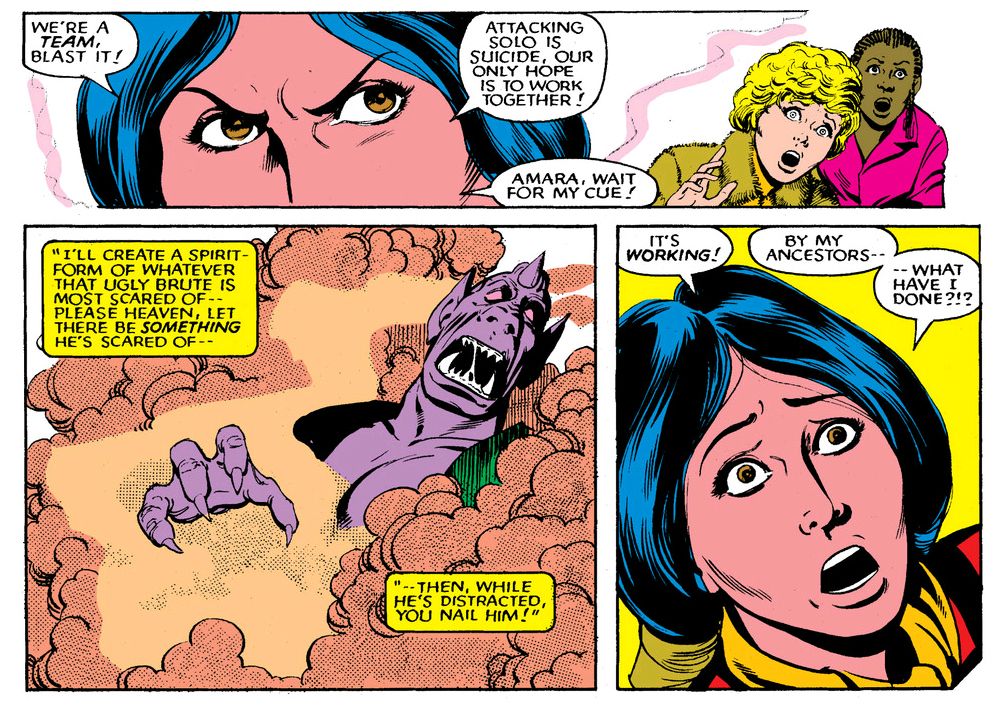

Dani first uses her mutant power-- which she has always found problematic-- to attack the creature with its greatest fear. Which turns out to be Dani herself. The masculine power fears the feminine one. The basis of gender relationships in Western culture is an unequal power dichotomy in which female strength is denied and negated in favor of the male out of fear and loathing, which includes a belief that menstruating women are somehow unclean. Here, using her innate strength, Dani comes closest to achieving victory. Dani, however, does not attempt to derive any deeper understanding of why the bear fears her as much as she fears it. Instead, she reverts to using the phallic arrow, striking the bear harmlessly in the neck, though she describes it as a "killing shot." If she intends to use the patriarchy's weapons against it, this proves to be a fatal decision. The bear easily sweeps the bow from her hands and batters Dani. She's able to injure the bear with a handheld arrow and earn a brief respite.

Escaping the bear's clutches, Dani retrieves her bow and fires another phallus into the one vulnerable opening the bear presents-- its mouth. Here, having penetrated the bear at last, she achieves a false victory and turns from her foe in premature triumph. In relying on a substitute penis, and denying herself the use of her own power-- despite its tantalizing glimpse of deeper wisdom-- Dani has not dealt fully with her own ambivalence towards her sexual maturation and gender role. As she walks away into the night, the bear's eyes open.

|

| Chris Claremont, scipt/Bill Sienkiewicz, art/Glynis Wein, colors (The New Mutants #18, August 1984) |

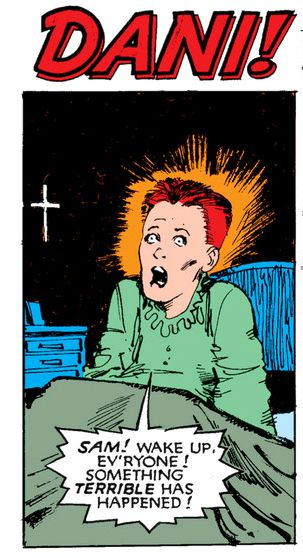

And, importantly, it's the virginal Rahne (Sienkiewicz clothes her in a prim, ruffled nightgown and places a cross behind her) who senses the danger and alerts the others. Dani has been struck down by the complexities and ambiguities of adulthood, but it's the most child-like of the New Mutants who reacts, having felt it psychically. Dani's friends run to help her-- Sam, the oldest boy, carries yet another phallus, what appears to be a shotgun-- and find Dani's gutted body staining white the snow of innocence with the red of her secret knowledge, which she is now in no shape to parse.

Not to equivocate, but simply as a response

to the richness of Claremont’s writing, I want to offer some alternate readings

to the “Demon Bear Saga.” The jumbled

mess above—no more than a B- effort if I were to turn it in to one of my old

lit professors—is just one way of reading the subtext. Here are some others, probably equally as

confused.

Hm.

That is equivocation. Oops!

In another reading, the bear isn’t a

stand-in for the patriarchy, but rather Dani’s rage at the patriarchy and her

enforced role within a system devised to limit her choices. Just as Dani’s mutant power allows her to

call forth the images of anyone’s greatest fears, her mutation allows her to

project her rage as a monstrous, destructive creature. This is supported by her guilt pangs at

having to carry the weight of her parents’ deaths. Why would Dani’s rage have struck them

down? Because they were—however protective

they meant it—participating in Dani’s diminution, the limiting of her spirit.

Let’s also consider the bear as

representing Dani’s sexual maturation in another way. At some point, Dani violated the incest taboo

by involving her parents—one or the other, or both—in a masturbatory

fantasy. Remember—she lives in guilt

because of transgression against her parents, not the other way around. She had what was essentially a fleeting,

blameless thought, one that’s probably quite common at the onset of sexual

yearnings, but one fraught with shame, and was perhaps caught by her parents during

the act. Humiliated, and with no one to

turn to, Dani becomes confused and self-loathing. Hence the bear, a stern, punishing father figure

she creates in reaction to these negative feelings. In this reading we can view Dani’s Danger Room

preparations also as a form of masturbation.

The X-Men use the unreal world of the Danger Room to rehearse real world

scenarios in much the same way we prepare ourselves sexually by self-exploration

and fantasization. To this end, as we’ve

already discussed, Dani seeks the counsel of the (sexually) experienced Magik.

In a related reading, the bear is sexual

maturation itself as loss of innocence.

Corruption of an innocent is a recurring Claremont theme—Magik is the

prime example, so much so he wrote an entire miniseries about just that. In Uncanny X-Men #160 (August 1982) and the Magik (December 1983-March 1984) series,

the devilish Belasco abducts child Illyana into Limbo where she literally loses

her soul by gaining premature knowledge of the world. Her innocence becomes corrupted by this

knowledge—one cover by John Buscema shows what’s essentially an underwear-clad

Illyana given diabolic aspect complete with horns and a phallic knife—and she literally

loses her soul. As a result, Illyana instantly

returns to the real world miraculously the immediately post-pubertal age of

thirteen years old. It’s hard to think

of another genre story that examines these themes so overtly.

And not just Illyana. For whatever reason, Claremont visits this

theme most frequently (but not exclusively… it just seems that way sometimes) upon

female characters. Jean Grey becomes

Dark Phoenix, Illyana becomes Magik, Selene attempts to seduce Dani into

becoming her evil sorcerer’s apprentice, super-innocent Rahne turns into a

nearly mindless avatar of light under the influence of drugs in a story

involving adult predators victimizing teen runaways, Storm from a powerful yet naïve

goddess into the worldly punk-look leader of the Morlocks, Madelyn Pryor

becoming the Goblin Queen, Dani again in Asgard going from high-flying Valkyrie

to evil, skeletal Odin-slaying version thanks to Hela. And those are just the ones I know by heart. We can approach the bear as another version

of this theme, with Dani’s war against it a struggle of innocence versus knowledge,

supported by the use of Magik as her teacher/helper, the red versus white color

scheme and the setting of the main confrontation within snowy woods.

So Dani responds negatively to this knowledge,

which, as it did with Magik, comes much too soon. Unready or unwilling, she rejects it, literally

and figuratively fights against it. Through

this struggle, she comes to terms with it and assimilates it within her healing

psyche thanks to the intervention of guide Magik and the others. This saves Dani and reaffirms her

friendships, but as many do to gain wisdom, Dani pays a heavy price—as do

others; this is a transformative wisdom in a literal sense—and temporarily loses

the ability to walk.

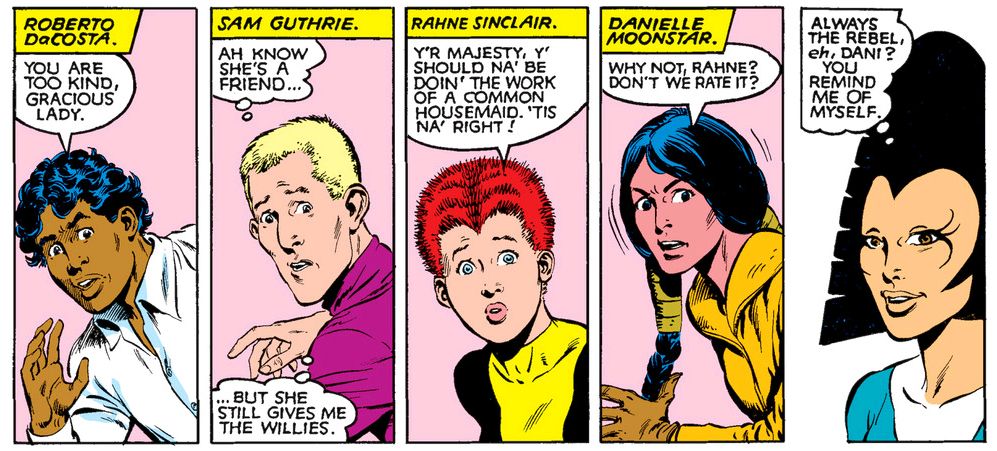

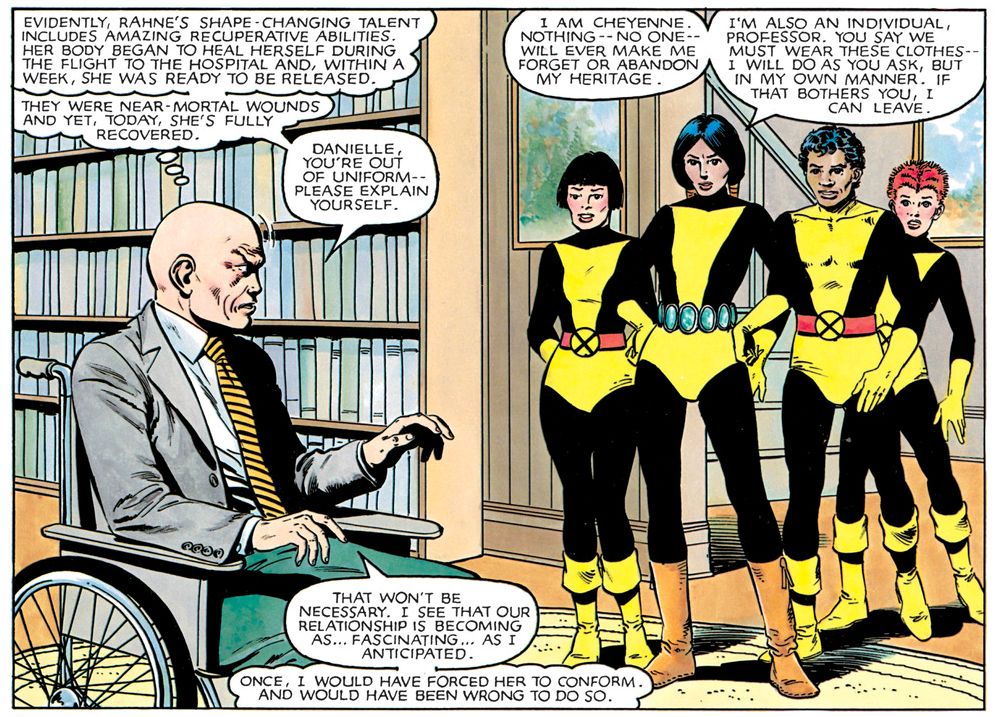

Then there’s the matter Dani’s

gendering. While Dani may or may not be

transgender, she does have an ambivalent response to her biological gender. When we first see her in Marvel Graphic Novel

#4: The New Mutants, she’s a solitary

figure, free from the misperceptions of others and, thus, allowed to clad herself

in attire that codes as male or, at most, ambiguously female. Throughout the subsequent comics, Dani frequently

wields her grandfather’s knife (a specific provenance it’s important to note,

as well as the knife’s phallic nature) and invokes the Cheyenne warrior

tradition and Claremont gives her clipped, militaristic speech at times. As she frequently casts off her clothes, she

is casting off the coding of the gender role in which she’s largely perceived

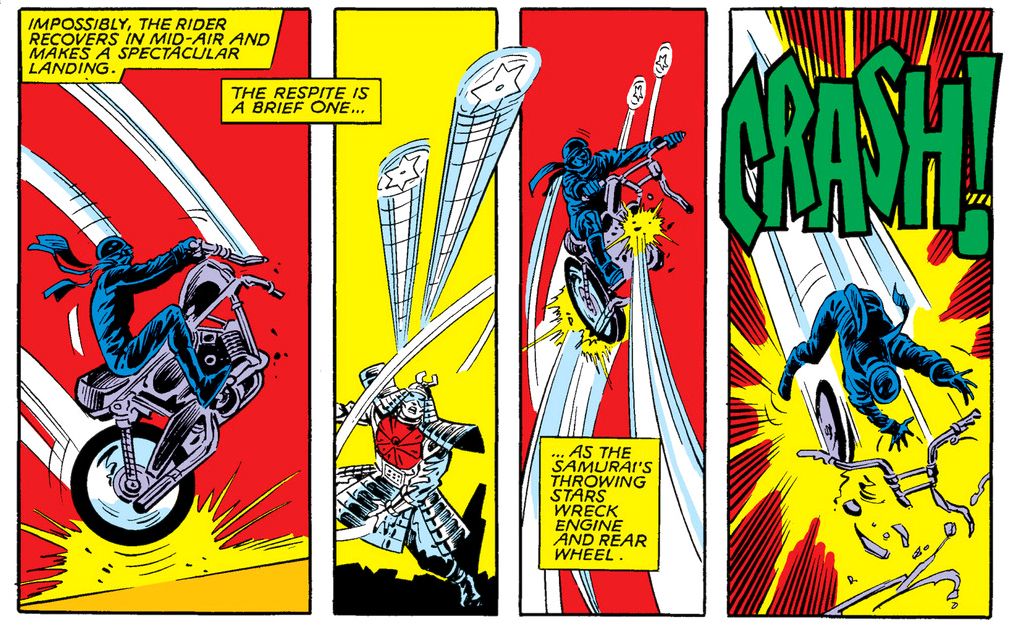

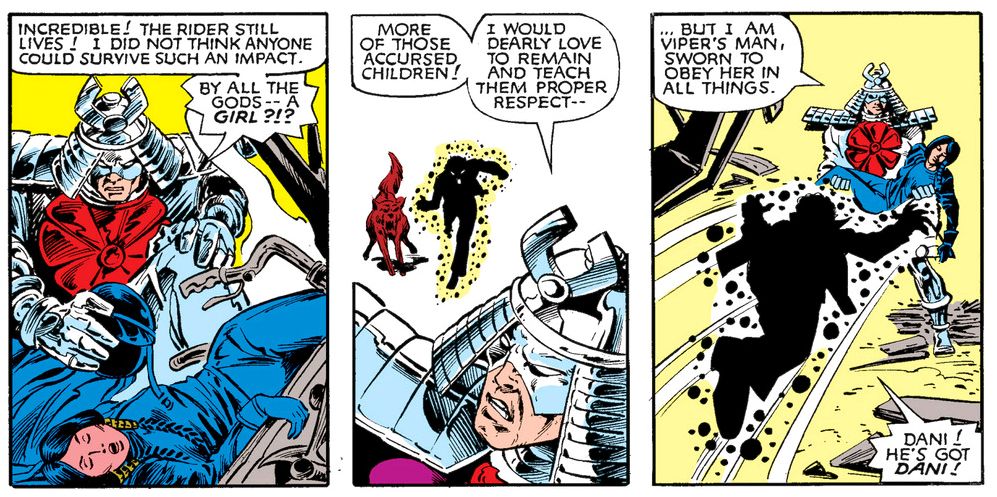

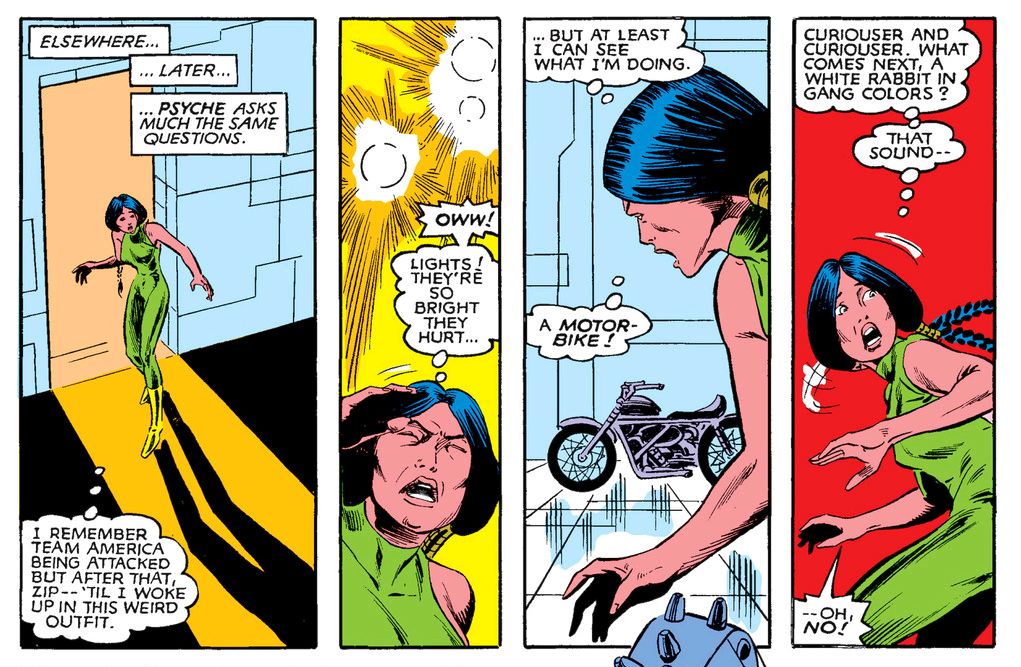

by her friends and the larger society in which she operates. In The New Mutants #5 (July 1983), Dani essentially becomes

a man when, under the influence of the exclusively male gestalt Team America,

she transforms into Dark Rider, with a firm and powerful machine between her

legs. Motorcycles traditionally code as

male, both in movies and in literature.

For a woman to ride one is seen as transgressive and empowering, tropes

exploited by B-movies and genre TV shows like James Cameron’s Dark Angel.

In the biker world, women are largely

constrained to the subsidiary role of “mama,” and the spot behind the

motorcycle’s rider is colloquially and dismissively referred to as the “bitch

seat.” But Dani becomes neither supporting player, nor domme a la Russ

Meyer. She's the Dark Rider and so characters

see Dani as a man. It’s not until she tumbles from the motorcycle-- suffered a figurative castration-- that they

can strip away the male disguise and reveal her true gender. Which is also a matter of perception in absence

of any definitive identification by Dani herself. And yet we must ask ourselves, why did this male

gestalt power single out Dani among the thousands of people attending the Team

America performance, including the biologically male members of the New Mutants

and bystanders?

As we’ve already seen, in the “The Demon Bear

Saga,” Dani symbolically genders herself largely male—albeit with elements of

the female-- in order to fight the bear.

Once again, the menstrual imagery comes into play as Dani struggles to

come to terms with her sexual maturation as a biologically functioning woman, a

limiting of options and something she dreads and fears in the same way young

transmen and transwomen struggle with their own unwelcome bodily changes and

processes. If we accept her Danger Room

sessions as symbolic masturbation, then we read the arrow as a phallus and

Magik as her fantasy-partner as Dani assumes the masculine, if not outright

male, role. While there are plenty of

story elements suggesting a largely heterosexual female identification for

Dani, Claremont introduces enough ambiguity to suggest Dani may not occupy any

definitive place within the gender or sexuality spectrum and the struggle with

the bear is a struggle with either herself or with society at large to

establish her own gender and sexual identity, free from all these imposed

concepts.

And all this is without even getting into

Dani’s frequent association with horses and horse imagery and symbolism! That’s a term paper unto itself.

While supporting multiple readings and interpretations-- the psychological, the mythic, as a gender critique and the literary-- this story also functions as a straightforward action narrative. Because this is a comic book, the bear isn't just a manifestation of Dani's psyche. It's also a very real external threat. What makes "The Demon Bear Saga" such a rich work (even though it does have a few of those terse Claremontian couplets in the narration-- "The bear misses. I don't."-- that lend themselves so easily to parody) is how well it assimilates all these aspects of storytelling while presenting a compelling and genuinely frightening read. While Marvel made good use of Claremont's "Dark Phoenix Saga" and "Days of Future Past" storylines, and similarly considered important enough for a graphic novel collected edition to call its very own, I rank this particular tale ahead of them because it digs deeper for its themes and motivations than simply "absolute power corrupts absolutely" or "prejudice is a bad thing."

And we're talking largely about the first half of the story. The second can no doubt be mined for just as much meaning. It takes place largely within a dreamscape and features the transformation of two minor characters into Native Americans. What can we make of this? Well, we'll just have to think about it for a while and see what we come up with.

Time to turn our gaze towards the future and another of my favorite characters...