Today, I got a surprise Myspace friend-request from a graphic novel. Now there's a sentence that would've been completely impossible to think of, much less type, when I first started reading comics at the tender age of 4. That was 1972, before anyone had ever considered using terminology like "Myspace" or "graphic novel" or "today."

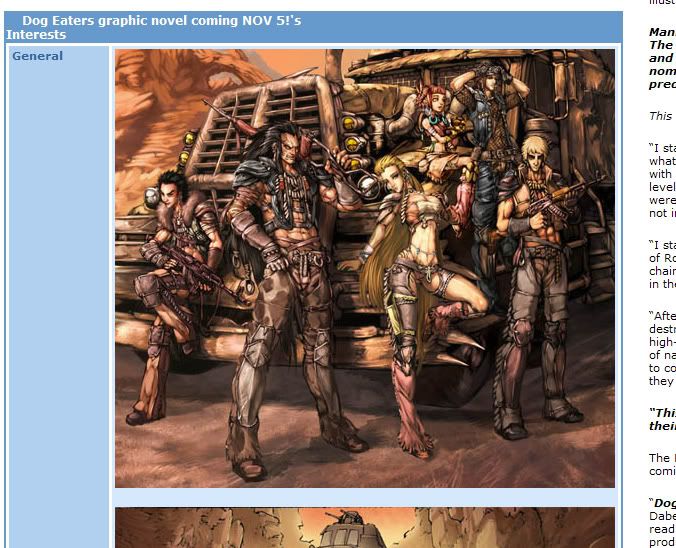

Today, I got a surprise Myspace friend-request from a graphic novel. Now there's a sentence that would've been completely impossible to think of, much less type, when I first started reading comics at the tender age of 4. That was 1972, before anyone had ever considered using terminology like "Myspace" or "graphic novel" or "today."Dog Eaters is a post-apocalyptic story from Dabel Brothers Publishing, adapted by Sean J. Jordan and Guillermo A. Angel from Malcolm Wong's original screenplay. I can't really comment on the story because I haven't read it yet, but Angel's manga-infused art is colorful and inviting.

And now I'm a-gunna tell ya exactly why, pilgrim.

I'm basically old school but I tend not to judge things based on their cultural influences. Either you can draw or you can't (although I find that dichotomy way too reductive... I personally can semi-draw) and if you have the basics down, "style" will follow.

Style, as the concept is generally understood, is vastly overrated. What many of us think of as style are merely the most superficial elements of drawing. Speedlines, cross-hatching, manga-esque eyes, slightly cartooned figures, heavy shadows, scratchy lines, almost geometric figures, "realism." These are the most visual aspects that hit your eye with immediacy, and we use them to describe what certain comic book artists' works look like. We call this his or her "style."

Judging artwork solely based on these elements is like choosing our friends based only on the clothes they wear. Sure, we get a few clues about who they really are from how people dress, but that doesn't tell us if they're good people or not. Doesn't give us the deep-down identity or selfhood that raises them from mere acquaintances to lifelong friends or even lovers, those things that make the relationship more than just pleasant but a necessity for our continuing happiness. Just as personality, compatibility and our personal concept of "goodness" are deeper criteria when choosing friends, so to is the underlying structure of drawing- the bones and musculature- more important than "style."

These basics show you whether or not a person can really draw, has a clue as to what drawing is all about. Anatomy, proportion, weight distribution, line of action, hierarchy of form, perspective, appeal, storytelling. One an artist masters this stuff, style takes care of itself. Too many comic book artists have this totally backwards. They also get confused because some of the true masters- people like Joe Kubert, Kojima Goseki, Takahashi Rumiko, Jack Kirby, Frank Frazetta- tend to distort or stylize the human form to suit their needs.

And even "realists" like Neal Adams tend to use heroic proportions. Classical guy non-realist John Buscema's heroes look like the leapt out of a Renaissance sketchbook (rather than off one of the porno stills some popular "photorealists" trace from these days... photorealism is not a be-all/end-all unto it self and again falls under the category "style" as superficiality).

Even Michaelangelo began stretching the human form towards the end of his career.

I'm not comparing Guillermo A. Angel to any of these. I'm just explaining to you why I might bitch about people using manga style elements to cover up bad drawing one day, then tell you Angel's manga-esque art looks attractive to me another. I don't do the knee-jerk rejection of manga-esque art; in fact, I think that's foolishness indeed and speaks volumes of the rejecter's personal prejudices and ignorance.

Some people like Adam Warren, and apparently Guillermo A. Angel, can do the colorful, fun manga look and even use non-traditional anatomy (check out how long the legs are, how small the heads, how thin the torso is on Angel's female characters) and still show they have a solid grasp on the underpinnings. That's what I pick up on, not necessarily superficial elements like "big eyes" or "overly long legs" (these aren't automatically negatives) or my least favorite of all "details."

Also sometimes mistakenly referred to as "shading," as in, "Manga artists don't know how to do shading!"

In comic book terms "details" frequently means meaningless cross-hatched lines everywhere even though they're neither building tone or modeling shadow on the figure or creating texture and space in the backgrounds. I don't want to raise a shitstorm by giving specific examples. I could- some of them would be quite popular and successful comic book artists beloved by many, and one is almost universally reviled these days (but I don't want to dogpile the guy.) Just check out almost every secondary Image artist of the 90s to see what I'm talking about. Visual noise.

In fact, one of the Big Guns of Image once said in an instructional (destructional would be more accurate, though) video that you should throw in a lot of that kind of stuff in place of actual drawing. He said it with a kind of "those stupid kids won't know the difference and they'll think you put actual effort into your schlock" wink that made me instantly turn off the video and give up on his work entirely.

Visual noise does not detail make. Real detail consists only of what's necessary to make the image work. That's why I appreciate people like Takahashi Rumiko, Jaime and Gilberto Hernandez, Alex Toth and Mike Allred (one day I want to write an entry about Allredrian anatomy... it fascinates me). They put down exactly what's necessary and little more. They have superficial differences, of course, but the basics are there, totally internalized and they don't need to truck in false detail. Al Williamson once inked an old Jack Kirby drawing for TwoMorrows' Jack Kirby Collector (I love that magazine) and crosshatched among the famous Kirby dots in the background. His reasoning? "It needed it." And he is right- it's not exactly pure Kirby but it definitely made the foreground figures pop by making them no longer in competition with the background.

Anyway, Angel's art looks pretty cool. It works. His figures are dynamic, his art is detailed to the correct level and in the right way, and he actually draws vehicles that look like they could work. They commented on my Myspace page with a friendly, art-filled message with some action packed stuff. Cool blood effects, bodies tumbling through the air, machine guns blazing. The more I see, the more I dig it. I wish I could comment more on the story, but I couldn't read the PDF preview. I'll try again later.

Based on what I have seen and just looking at the art, I'd like to check out a few more preview pages. I'm not a big sci-fi/fantasy person. I tend to stop and start at Ray Bradbury and Kurt Vonnegut. But Dog Eaters seems to do that Mad Max punkish-motor-tribes-in-a-desert-wasteland thang I love, and it it's also another thing I tend to like- a finite story. One with a beginning, middle and end. Which hopefully means character development going from point A and coming to its logical conclusion at point Wherever without extending the story past its natural stopping point into absurdity and continuity insanity, a la most serialized comic book monthlies. Some of Malcolm Wong's political and social concerns are also my own, so I give him some credit for developing the book from those, too.

According to MySpace, besides his Dog Eaters screenplay, Malcolm Wong has directed music videos here in Japan... and he and his wife are also responsible for the rebirth of the fashion doll, Blythe. That's also pretty cool. Actually, taken altogether, that's some high-powered cool.

And the final cool thing about this? Thanks to Dog Eaters' friendship, I was able to friend Diablo Cody, kick-ass screenwriter of Juno, one of my favorite movies. In fact, in a year overrun with good superhero action movies I definitely enjoyed, Juno remains healthily ensconced on top of my list as Best Movie Released in Japan in 2008.

Thanks, Dog Eaters!

PS- One day I'll re-explain why I generally reject using the term manga as jargon specifically referring to Japanese comics or Western comics drawn in similar styles. I just use it here as shorthand and out of laziness.